“Our radar has MARPA.” — Every marine electronics salesperson, confidently overselling what that actually means.

The Acronym Confusion

Walk into any chandlery, and you’ll hear radar systems marketed with impressive-sounding acronyms. ARPA. MARPA. Target tracking. Collision avoidance. The brochures show crisp displays with neat little vectors pointing away from your vessel, promising automated safety.

But there’s a fundamental difference between what commercial vessels have been using for decades and what recreational sailors get—a difference that matters far more than most sailors realize.

ARPA: The Commercial Standard

ARPA stands for Automatic Radar Plotting Aid. It’s been mandatory on commercial vessels since the 1980s following a series of catastrophic collisions. The IMO (International Maritime Organization) sets strict performance standards for ARPA systems, codified in Resolution A.823(19) and subsequent amendments.

A true ARPA system must:

| Requirement | IMO Standard |

|---|---|

| Simultaneous targets | Minimum 20 targets (often 40+) |

| Auto-acquisition zones | Automatic detection in designated areas |

| Target tracking accuracy | CPA within 0.3nm, TCPA within 1 minute |

| Trial maneuver | Simulate course/speed changes before execution |

| Lost target alert | Immediate notification when tracking fails |

| Guard zones | Alarm when any target enters defined area |

Commercial ARPA systems are integrated with the ship’s gyrocompass and speed log, providing ground-stabilized or sea-stabilized tracking. They’re operated by trained officers who’ve spent weeks learning radar interpretation. They’re backed by redundant systems and maintained to classification society standards.

MARPA: The Recreational Compromise

MARPA stands for Mini Automatic Radar Plotting Aid. The “Mini” tells you everything you need to know.

MARPA was developed for recreational and small commercial vessels that couldn’t justify the cost or complexity of full ARPA systems. It provides a subset of ARPA functionality at a fraction of the price.

| Feature | ARPA (Commercial) | MARPA (Recreational) |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous targets | 20–100+ | 10–30 |

| Target acquisition | Automatic + Manual | Manual only (usually) |

| Heading input | Gyrocompass (0.1° accuracy) | Fluxgate/GPS (1–3° accuracy) |

| Speed input | Doppler speed log | GPS SOG or paddle wheel |

| Trial maneuver | Yes | Rarely |

| Auto-acquisition zones | Multiple programmable | Limited or none |

| IMO type-approved | Yes (mandatory) | No |

| Operator training required | Yes (STCW certified) | No |

| Typical price | $15,000–$50,000+ | $2,000–$8,000 |

The price difference reflects a reality: MARPA is designed to be “good enough” for recreational use. But “good enough” assumes certain conditions that don’t always hold.

The Manual Acquisition Problem

Most MARPA systems require you to manually select which targets to track. You see a blip on the screen, you move a cursor to it, you press a button, and the system starts calculating its course and speed.

This works fine in light traffic. But consider:

- A busy shipping lane with 15 vessels

- A night watch with one tired crew member

- Degraded visibility in rain or fog

- A fast-moving target that appears suddenly

The system can’t warn you about a collision risk until you’ve told it to track the threat. By the time you’ve manually acquired all relevant targets, the situation may have changed. By the time you’ve interpreted the vectors, you may be out of maneuvering room.

Commercial ARPA systems solve this with automatic acquisition zones: define an area, and any target entering that zone is automatically tracked and evaluated. MARPA systems rarely offer this capability—and when they do, it’s often limited and unreliable.

The Disappearing Target Problem

Even after you’ve manually acquired a target, the battle isn’t won. Radar returns from small vessels—especially in any kind of sea state—are notoriously intermittent.

Here’s what actually happens:

- You spot a blob on the radar display

- You manually associate it with a MARPA target

- The system starts tracking—course, speed, CPA, TCPA

- A few seconds later, the blob disappears into wave clutter or rain noise

- The system loses the target and displays “TARGET LOST”

- The blob reappears on the next scan… but it’s no longer associated with your target

Unless you manually re-acquire that blob—assuming you even notice it’s back—the system treats it as an unknown contact. All the tracking data you had is gone. The calculations start from zero.

In confused seas or rain, a weak radar return might appear on one antenna rotation, vanish for two or three rotations, then reappear slightly displaced. For MARPA to track it, you have to keep re-acquiring it. The automation is only as persistent as the human operating it.

This creates an impossible situation: to get any value from MARPA in degraded conditions, you need to be constantly watching the screen, constantly re-acquiring lost targets, constantly interpreting unstable vectors.

Which raises a question nobody wants to ask.

Is Your Head in the Right Place?

If MARPA requires constant attention to be useful, is it actually improving safety—or is it keeping the watchkeeper’s eyes fixed on a screen instead of the horizon?

Aviation figured this out decades ago: you either fly looking outside, or you fly looking at instruments. Never both.

The VFR/IFR Lesson

Pilots operate under two distinct regimes:

- VFR (Visual Flight Rules): You navigate by looking outside. The horizon is your reference. You see traffic with your eyes.

- IFR (Instrument Flight Rules): You navigate by instruments. Your eyes are on the panel. You trust the gauges, not what you think you see.

The critical insight is that mixing the two is lethal.

When a VFR pilot flies into clouds (Instrument Meteorological Conditions, or IMC), they instinctively try to do both—glance at instruments, look outside, back to instruments. The result is spatial disorientation, loss of control, and death.

VFR into IMC: The Statistics

- 72–92% fatality rate for VFR pilots who enter IMC conditions

- 178 seconds—less than 3 minutes—before an untrained pilot loses control

- 14× higher fatal accident rate when flying in IMC vs. visual conditions

- 94% fatality rate when spatial disorientation is involved

Sources: NTSB accident data 2008–2020; FAA VFR into IMC study; AOPA Air Safety Institute

The lesson aviation learned—written in the blood of thousands of pilots—is absolute: commit to one mode or the other. If you’re flying visually, your primary reference is outside. If you’re flying on instruments, your eyes never leave the panel. The moment you try to do both, you’re in the accident statistics.

And Now Consider Sailing

COLREG Rule 5 requires a “proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means.” The intent seems reasonable: use every tool at your disposal.

But think about what this actually demands: you’re supposed to watch the radar screen, interpret MARPA vectors, monitor AIS targets, and maintain a visual lookout—all simultaneously. On a shorthanded yacht at 3 AM, you’re doing what kills pilots: mixing visual and instrument reference, constantly switching between paradigms, never fully committed to either.

On commercial vessels, this is solved by crew rotation and bridge team management. One officer watches the radar. Another scans the horizon. The task is divided because humans can’t do both well. On a cruising yacht, you’re both of those people—and you can’t be in two places at once.

The cruel irony: the technology that was supposed to help you see threats is keeping your night vision ruined and your eyes pointed at a screen instead of the sea. You’re neither properly visual nor properly instrument-referenced. You’re in the maritime equivalent of VFR into IMC—and there’s no accident statistic to tell us how dangerous that is, because nobody’s counting.

The Heading Accuracy Problem

ARPA calculations depend critically on knowing your own vessel’s heading. Commercial ships use gyrocompasses accurate to 0.1 degrees. Recreational boats typically use fluxgate compasses or GPS-derived heading, which can have errors of 1–3 degrees or more.

This might not sound like much. But consider:

At 6 nautical miles range, a 2-degree heading error translates to a position uncertainty of approximately 0.2 nautical miles (370 meters) for the target’s predicted position.

That’s enough to turn a “safe pass” into a close-quarters situation—or worse, to make you think a close-quarters situation is a safe pass.

The Regulation Gap

Commercial vessels are subject to SOLAS (Safety of Life at Sea) regulations. Depending on tonnage and route, they must carry:

- Two independent radar systems (different frequencies)

- ARPA on at least one radar

- AIS transponder

- ECDIS (Electronic Chart Display)

- VDR (Voyage Data Recorder)

Recreational vessels? In most jurisdictions: nothing. No radar required. No ARPA. No AIS transponder (receivers are optional). No training certification. No equipment standards.

The philosophy is clear: pleasure sailing is a personal choice, and sailors accept the risks. But this creates an asymmetry when recreational and commercial vessels share the same waters.

Can You Buy True ARPA for a Pleasure Boat?

Yes—sort of. But the options are limited and expensive.

Among recreational-grade radars, Furuno is the only manufacturer that offers what could fairly be called true ARPA functionality. Their DRS4DL+ and NXT series radars can automatically acquire and track up to 40 targets, with the option to manually add 60 more. As soon as the radar powers on, it starts looking for targets without waiting for you to point at each one.

Furuno’s system—which they market as “Fast Target Tracking” rather than ARPA, perhaps to avoid regulatory implications—actually works. Reviews consistently note that the tracking speed and course data closely match Class A AIS transponder information from the same vessels.

Other manufacturers are more cautious in their claims:

| Manufacturer | Model | Auto Acquisition | Price (2024) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Furuno | DRS4DL+ / NXT series | Yes (40+ targets) | $2,500–$4,000+ |

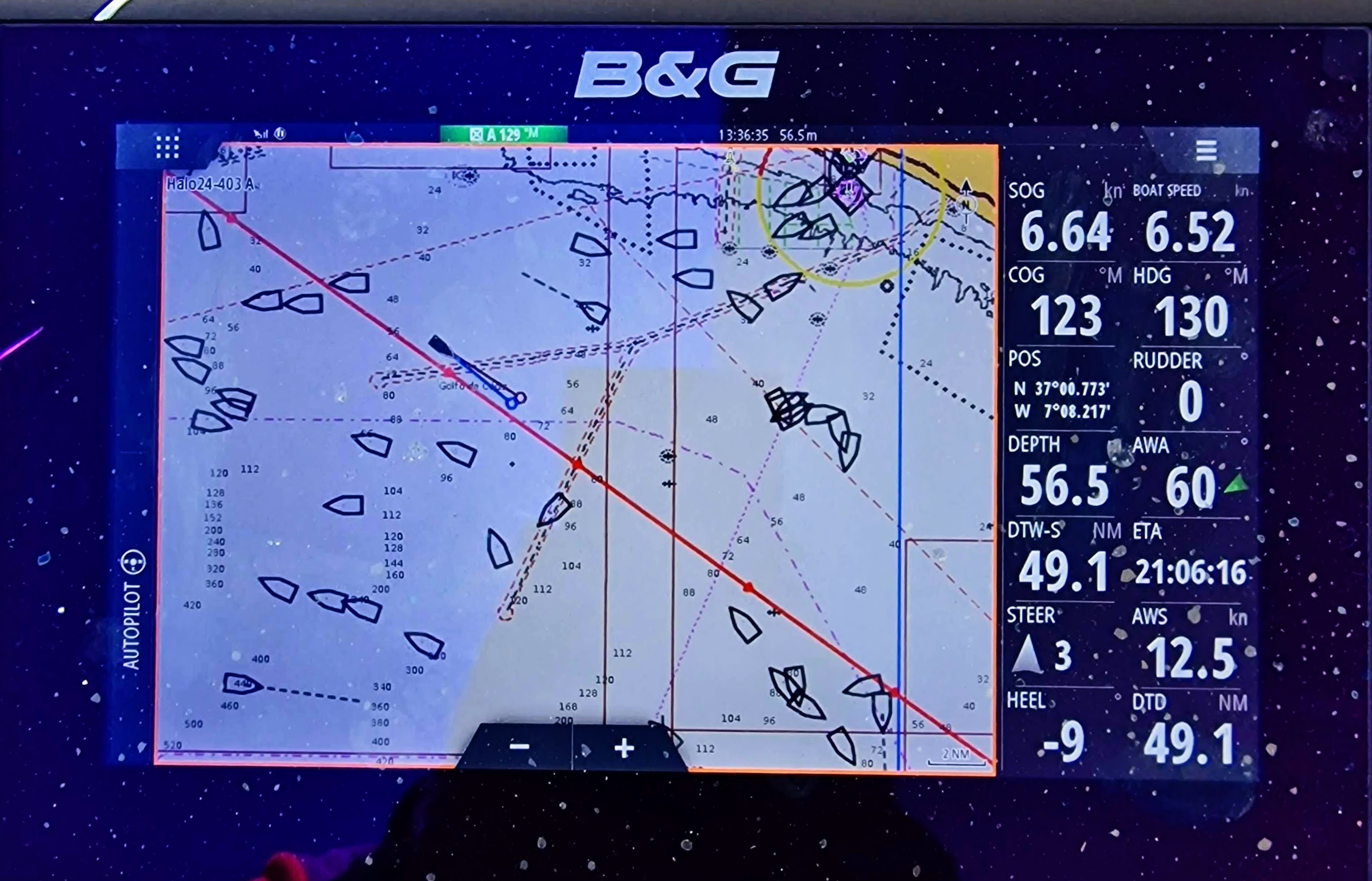

| Simrad | Halo 20+ | Limited (2 zones only) | ~$2,300 |

| Raymarine | Quantum 2 | Safety zones only | ~$2,260 |

| Garmin | Fantom 18x/24x | Manual MARPA only | ~$2,200 |

So if you want true automatic target acquisition in the recreational market, you’re largely limited to Furuno—and you’re paying a premium for it.

The Uncomfortable Truth: The Mast Problem

Now we arrive at the intrinsic limitation that no amount of technology can overcome.

On a sailboat, the radar antenna is typically mounted on a pole, arch, or the mast itself—but it must contend with that large aluminum or carbon fiber spar directly in front of it. The mast creates a radar shadow: a dead zone where radar energy cannot penetrate.

Let’s do the geometry properly.

The Dead Angle Calculation

The shadow angle depends on two factors: mast diameter and radar mounting distance from the mast.

| Mounting Position | Distance to Mast | Dead Angle (250mm mast) |

|---|---|---|

| Mast-mounted bracket | 0.5m | ~28° |

| Mast-mounted pole (aft) | 1.0m | ~14° |

| Mizzen mast (ketch) | 3m | ~5° |

| Stern arch | 8–10m | ~1.5–2° |

The formula is simple: Dead Angle = 2 × arctan(mast radius / distance to radar)

But the mast isn’t the only obstruction. Add to that:

- Forestay and headsail furler—typically 50–80mm diameter, creating additional shadow forward

- Shrouds—multiple wire stays on each side, each adding small shadows

- Spreaders—horizontal aluminum tubes that block at specific angles

- Radar reflector—ironically, mounted on the mast to make YOU visible, blocking YOUR radar

- Boom—when not centered, adds another shadow sector

The Real Blind Sector

For a typical mast-mounted radar on a 40-foot sloop, the combined dead angle from mast, forestay, and rigging can easily reach 15–30 degrees. That’s not a sliver—that’s a significant chunk of your forward arc where vessels are completely invisible to radar.

What This Means at Sea

Let’s translate angles into real-world consequences:

- A 20-degree blind sector at 3nm spans approximately 1.0 nautical mile (1.9 km) of ocean

- A fast ferry traveling at 30 knots covers this distance in about 2 minutes

- A container ship at 20 knots crosses your blind sector in about 3 minutes

- If that vessel enters your blind sector and stays there as you both move, you will never see it on radar

This isn’t a theoretical concern. Constant-bearing, decreasing-range (CBDR) collision courses are precisely the geometry where a target stays in the same relative position—including, potentially, behind your mast.

The Probability of Missing a Collision

Let’s calculate the odds that a potential collision is invisible to your radar.

A vessel on a collision course can approach from any bearing. The probability that it happens to be in your blind sector is simply:

That’s roughly 1 in 18.

The Cumulative Risk

A 5.6% chance per encounter doesn’t sound alarming—until you consider a cruising lifetime. After 12 close-quarters situations, you have a 50% chance of having encountered at least one invisible threat. After 40 encounters, that probability rises to 90%.

The mathematics are unforgiving: over enough time at sea, the blind sector will hide something important. The question isn’t if—it’s when.

The Power Problem: Why Two Radars Isn’t Really an Option

The obvious solution to the mast blind sector is to install two radars—one forward, one aft—positioned to cover each other’s shadows. This is exactly what commercial vessels do with their dual-radar requirements. But for a cruising sailboat, this solution runs into two brutal realities: cost and power.

Two Furuno DRS4D-NXT radars with true ARPA capability? That’s $5,000–$8,000 just for the hardware—before installation, displays, and cabling.

But the purchase price is the easy part. The hard part is keeping them running.

Modern solid-state radars—marketed as “4G” or “Pulse Compression” (the “4G” has nothing to do with cellular networks; it’s pure marketing)—are dramatically more efficient than their magnetron predecessors. But “more efficient” doesn’t mean “free.”

| Radar Model | Transmit Power | DC Power Draw (Transmit) | Amps @ 12V |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raymarine Quantum 2 | 20W | 17W | ~1.4A |

| Simrad Halo 20+ | 25W | ~25W | ~2.1A |

| Garmin Fantom 18x/24x | 50W | 33W (normal) | ~2.75A |

| Furuno DRS4DL+ (true ARPA) | 4kW peak | 23W | ~1.9A |

| Furuno DRS4D-NXT (true ARPA) | 25W | 30–48W | ~2.5–4A |

These numbers don’t sound catastrophic—until you consider what they mean over a 24-hour period.

And here’s the critical point that many modern sailors miss: the problem isn’t storing the power—it’s generating it.

Yes, lithium batteries have revolutionized energy storage on boats. A 400Ah lithium bank can deliver its full capacity without damage, charges faster, and weighs half as much as lead-acid. Storage is essentially solved.

But you still have to put those electrons into the battery. And that’s where the mathematics become brutal.

The Sailboat Power Budget Reality

A typical 40-foot cruising sailboat has a daily power budget of approximately 100–150 amp-hours on passage. Here’s where it goes:

| Consumer | Power Draw | Hours/Day | Daily Ah |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refrigeration | 5–8A | 12–16 | 60–100 |

| Autopilot | 2–5A | 24 | 48–120 |

| Chartplotter/MFD | 1–2A | 24 | 24–48 |

| Navigation lights | 1–3A | 12 | 12–36 |

| VHF/AIS | 0.5–1A | 24 | 12–24 |

| Instruments/misc | 0.5A | 24 | 12 |

| ONE radar | 2–3A | 12–24 | 24–72 |

Total daily consumption: 190–410 Ah—often exceeding what most sailboat battery banks and charging systems can sustainably provide.

Two Radars = Double the Problem

Adding a second radar to cover the mast blind sector means another 24–72 Ah/day. For a boat already struggling to balance its power budget, that’s the difference between making port with reserves and running the engine to charge batteries mid-passage.

The Generation Gap

How do cruising sailors generate power underway? Let’s look at realistic numbers:

| Generation Source | Typical Output | Daily Yield (Realistic) |

|---|---|---|

| Solar panels (300W installed) | ~200W effective | 60–100 Ah (5 hrs sun) |

| Hydrogenerator (towed) | 5–10A @ 6+ knots | 50–100 Ah (if sailing fast) |

| Wind generator | 2–8A @ 15+ knots | 30–80 Ah (variable) |

| Engine alternator | 50–100A | Burns diesel—not sustainable |

A well-equipped cruising yacht with solar, hydro, and wind generation might produce 150–250 Ah per day in good conditions. In overcast weather, light winds, or when sailing slowly? Half that—or less.

Two ARPA Radars: The Math

Two Furuno DRS4D-NXT radars running 24 hours: 120–192 Ah/day (at 2.5–4A each).

That’s potentially more than your entire generation capacity—just for radar. Before refrigeration, autopilot, lights, instruments, or anything else.

Commercial vessels solve this with generators running 24/7, shore power when berthed, and electrical systems designed for kilowatts of continuous draw. A container ship’s auxiliary generator produces more power than a hundred cruising sailboats combined.

So while “install two radars to eliminate the blind sector” is technically possible, the power mathematics make it impractical for any vessel relying on renewable generation. You can have lithium batteries capable of storing a week’s worth of power—but if you can’t refill them, they’re just expensive ballast.

The second radar remains a luxury few can afford—not in purchase price, but in the ongoing cost of generating the electrons to keep it spinning.

Why This Can’t Be Fixed

Some radar manufacturers recommend mounting the scanner on a pole behind the mast, or on the stern arch. This moves the blind sector, but doesn’t eliminate it—the mast is still there, still blocking radar returns from certain angles.

The only true solution would be multiple radar antennas positioned to cover each other’s blind sectors—exactly what commercial vessels do with their dual-radar requirements. But recreational sailboats rarely have the space, power budget, or budget-budget for redundant radar installations.

Commercial ships don’t have this problem. Their radar antennas are mounted high above any obstructions, with clear 360-degree visibility. Sailboats, by their very nature, have a large vertical structure in the middle of the boat that cannot be moved.

The Combined Effect

So here’s what the recreational sailor actually has:

| Factor | Reality |

|---|---|

| Target tracking | MARPA—fewer targets, manual acquisition, less accurate |

| Heading accuracy | Degraded by fluxgate/GPS limitations |

| Coverage | Blind sector caused by mast |

| Training | Optional (usually none) |

| Redundancy | Single system, no backup |

| Result | A compromised system operated by untrained users with a built-in blind spot |

This isn’t to say MARPA is useless—it’s a valuable tool when properly understood and correctly employed. But it’s not a substitute for vigilance, seamanship, and the understanding that no technology can see through a mast.

What This Means for You

If you’re sailing with MARPA:

- Know your blind sector. Determine where your mast blocks radar coverage and check those angles visually.

- Don’t rely on automatic alerts. Your system may not have auto-acquisition, and even if it does, targets in the blind sector won’t trigger alarms.

- Cross-reference with AIS. AIS doesn’t have blind sectors—but not all vessels transmit AIS.

- Maintain a visual lookout. Mark One Eyeball remains the most reliable collision-avoidance system ever invented.

The Bottom Line

MARPA gives recreational sailors a taste of what commercial vessels have had for decades. But it’s a simplified, compromised version of a system designed for a different operational context.

And even the perfect ARPA system—with full automation, gyrocompass input, and trained operators—would still have one fundamental problem on a sailboat:

It can’t see through the mast.

In the ongoing game of maritime safety, that’s the limitation you can’t engineer away. The only solution is to remember it’s there—and to look where your radar cannot.

Leave a Reply